Orientalism, Absence, and Quick Firing Guns:

The Emergence of Japan as a Western Text (5/5)

III. The Landscape and the Position of the Observer

My people have been sending artistic treasures to Europe for some time, and were regarded as barbarians, but as soon as they showed themselves able to shoot down Russians with quick-firing guns they were acclaimed as a highly civilised race.—Japanese diplomat, commenting on reaction to the Japan-British Exhibition of 1910, adapted from The British Press and the Japan-British Exhibition

In ‘The Discovery of Landscape’, the opening chapter of Karatani Kôjin’s Origins of Modern Japanese Literature, Karatani argues that ‘landscape’ (fûkei in the Japanese) was a ‘structure of perception’ (ninshiki no fuchi) before it became a representational convention. What Karatani has in mind in using these terms in this way is a fundamental rethinking of the epistemological landscape of the third decade of the Meiji period, when Japanese art and literature, following Japanese institutions and infrastructures, became ‘modern’. Landscape, Karatani argues, did not exist in Japan before the Meiji period, but once it ‘emerged’, or had been ‘discovered’, it ‘fundamentally altered’ the ways Japanese artists and writers could perceive the world, so that even the ‘nativist scholars’ (kokugakusha) who ‘searched for a landscape that predated ‘landscape”’ were caught in the ‘contradiction of being able to envision it only in relation to “landscape”’. [1] Ultimately Karatani’s argument is a provocative critique of modernity itself, its ‘extreme interiorization’ and the emergence of its ‘landscapes from which we [have] become alienated’, but his understanding of landscape as a ‘semiotic configuration’ (kigorontekina fuchi) helps to explain not only the cultural disjunction that led to the emergence of a modern Japanese literature, but also the development of the historical landscape from within which twentieth-century English-language poetry influenced by Japan emerged.

Literary critics who have addressed the subject have tended to focus on other matters, and to treat literary works responding to Japan as dissociated from time, place, culture, history, and even other texts. One recurring line of argument has it that the work fails on the grounds that British, Irish, and American writers turning to Japan have not understood the nature of their Japanese antecedents: Fletcher’s poems derived from ukiyoe fail because they are ‘not . . . truly Japanese’; Lowell’s ‘hokku’ disappoint because they lack ‘the essential quality’ of the form; Pound’s mediations of Japan are unsuccessful because he was ‘unacquainted with Japanese affairs’; Yeats’s dance plays are wanting because he did not understand the nô. Others have seen the same work through different eyes: Fletcher’s poems reflect the ‘spirit’ of haiku and Zen; Lowell’s writing derives from an ‘Oriental aesthetic consciousness’; Pound attained to the ‘essence of the haiku’ and the ‘Zen mood’ of yûgen; Yeats ‘reached the essence . . . of Oriental life’ and his dance plays the ‘essential structure’ of the nô. [2]

The problem with these and related interventions into the critical discourse is that they neglect history, or, rather, in Karatani’s terms, regard work that emerged from and became a generative part of a historical landscape as somehow preceding or superseding the landscape itself, as if literature were a universal aesthetic realm, or the significance of a literary work depended on the degree to which it corresponds to an a priori essence. Pound, Yeats, Fletcher, Lowell, Aiken, Aldington, Bynner, Flint, Ficke, and many of the other writers associated with the emergence of the new poetry in Britain and America in the second decade of the century, turned to Japan, or what they understood to be of Japan, at critical junctures in their writing and thought, and the period marks the first great emanation of a Japanese Muse in English literature, but her lineage was more mixed than generally has been acknowledged, and the work over which she presided was no less coloured by two and a half centuries of Japanese seclusion than ‘Ballade of a Toyokuni Colour Print’, nor any less bound to the exigencies of politics and power than the British press responding to the Japanese seizure of the ancient empire of Korea.

The cultural disjunction that Karatani describes has its closest counterpart in the West in the outbreak of war in Europe in August 1914. In Eric Hobsbawm’s history of the modern world that month marks the end of the ‘Age of Empire’ and the beginning of the ‘Age of Extremes’, a transformation from the orthodoxies and commonplaces of the ‘long nineteenth century’ to a new order fashioned by those who came of age in the twilight of empire. Mao Tse-tung, Ho Chi-minh, Tito, Franco, de Gaulle, Hitler, and Nehru were in their twenties, Roosevelt, Mussolini, Stalin, Adenauer, and Keynes their thirties, Churchill, Lenin, and Gandhi forty, forty-four, and forty-five. [3] In Japan in that third year of Taishô, the age of Great Righteousness, Tôjô Hideki was twenty-nine, Hirohito, the crown prince, thirteen. Of figures in the ‘field of culture’ Hobsbawm notes only that nearly half of those given notice in the Dictionary of Modern Thought were ‘active in 1880-1914 or adult in 1914’, but particular names come easily to mind. Among the contemporaries of de Gaulle, Adenauer, and Churchill were Cocteau, Stravinsky and Mondrian, Heidegger, Picasso, and Diaghilev, Gramsci, Bartók, and Proust. And in the field of English literature D. H. Lawrence and James Joyce, twenty-eight and thirty-two, were struggling against poverty in London and Trieste, T. S. Eliot, twenty-five, was at work on a Harvard doctor’s thesis that would never be presented, and two poets who had spent the previous winter at a cottage in Sussex working through rough translations from the fourteenth-century drama of Japan, Ezra Pound and W. B. Yeats, twenty-eight and forty-nine, despite earlier notorieties and the latter’s reputation as a figure from the Celtic Twilight, were forming the sensibilities and refining the techniques that would shape their most remarkable work.

The discovery of Japan by the English-language writers of this period, as in the nineteenth century, was part of a larger turning toward the non-Western world, but even more than in the nineteenth century the Japan to which Europeans and Americans were able to turn occupied a unique place in the map of Western consciousness. As early as the sixteenth century European artists and literati had found in the exotic much they believed wanting in Europe itself, ‘a sort of moral barometer’, Hobsbawm calls it, of European civilisation, but in the popular imagination of the age of empire the moral and practical superiority of Western knowledge was largely unquestioned. Hobsbawm notes the ‘intellectually-minded’ administrators and soldiers of empire who produced a body of scholarship that at its best respected and derived instruction from non-Western cultures, and a European secular left that was ‘passionately devoted to the equality of all men’, but also that the ‘the idea of superiority to, and domination over, a world of dark skins in remote places’ was undeniably popular, [4] and the nineteenth-century Western encounter with Japan did not fundamentally alter the structure of this perception, Japonisme and Japanese modernisation notwithstanding. When John Ruskin saw Japanese jugglers performing in London in 1867 he could not escape the impression that he was in the presence of ‘human creatures of a partially inferior race’, representative of ‘a nation afflicted with an evil spirit, and driven by it to recreate . . . a certain correspondence with the nature of lower animals’, [5] and even as Japan emerged both as Western fashion and modern state reminders were common in the British press that the Japanese were ‘steeped in feudalism’ or ‘tainted with cruelty’, or that ‘the administration of justice, as understood by us, is wholly foreign to them’, or even, toward the end of the century, that Japan owed her admittance to the ‘comity of civilized States’ to the ‘harsh discipline’ of the West, for ‘had not the spur of her impaired sovereignty been constantly forced into her side’, the Times found late in 1899, ‘her rate of advance would have been much slower’. [6]

In Britain this discourse began to change early in the twentieth century, with the expansion of European political rivalries outside Europe itself and the emergence of Japan as an ally. A shift in the position of the observer is evident in the popular journalism of the day, which after the Boxer Protocol tended to patronise the Japanese less often and less overtly, and in popular monographs such as Henry Dyer’s Dai Nippon, which posited Japan as ‘the Britain of the East’, and in poems such as George Barlow’s ‘Anglo-Japanese Treaty Sonnet’:

When Hate’s black standard is at length unfurled

And stored-up rancours smite thee,—when from France

Springs Waterloo’s for ever poisoned lance

And Germany, like a huge snake uncurled,

Gleams fierce and fork-tongued,—when from Russia hurled

Dark armies down the Asian vales advance

Pitiless, immense, barbaric,—when no glance

Meets thine of friendship, not through all the world

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Who shall stand by thee? This thy loving dwarf,

Thy staunch ally, thy saviour, swart Japan. [7]

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

||||

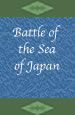

| But Dyer’s Britain of Asia and Barlow’s loving dwarf are no less purely constructs of the Western imagination than Henley’s maids at Miyako or W. S. Gilbert’s Poo-Bah. It was only when the Japanese proved themselves able to shoot down Russians with quick-firing guns that the structure of Western perception was fundamentally altered. The Japanese had ‘astonished mankind’ and ‘placed Asia in a new light before the World’, Henry Hyndman wrote as the Portsmouth Accords were being drafted, and he was right. Images: Quick Firing Guns; headlines; 1905 sketch depicting the Meiji Emperor and Tsar Nicholas II shaking hands, Theodore Roosevelt, who had mediated the Portsmouth agreement, looking on. | ||||

But Dyer’s Britain of Asia and Barlow’s loving dwarf are no less purely constructs of the Western imagination than Henley’s maids at Miyako or W. S. Gilbert’s Poo-Bah. It was only when the Japanese proved themselves able to shoot down Russians with quick-firing guns that the structure of Western perception was fundamentally altered, and by a text not written in Europe or North America. Hobsbawm notes that Europeans had long admired the fighters of the non-Western world who could be put to use in colonial armies—Gurkhas, Sikhs, Afghans, Beduin, and Berbers, among others—and that the Ottoman Empire had ‘earned a grudging respect’ in Europe because even in decline its infantry could withstand European armies, [8] but the defeat in war of a modern European power by a non-white and non-Christian state unsettled orthodoxy, polarised opinion, and as never before in modern history brought the political reality of a non-Western state fully into the public consciousness of Europe and North America. ‘The story of the last ten days [has] fallen upon the Western world with the rapidity of a tropical thunderstorm’, the Times reported after the Japanese attack on Port Arthur, for Japan had maintained ‘in Eastern waters a naval strength superior to [Britain], and . . . at a pinch [could] put half-a-million of men into the field’, but nonetheless the West had been ‘pleased to look upon the Japanese through the eyes of the aesthetic penman, and thought of the nation as a people of pretty dolls dressed in flowered silks . . . until the 10th of the present month [February 1904], when the truth became known’. Some months later, as the Portsmouth accords were being drafted, Henry Hyndman wrote in the journal of the British Social Democratic Federation that the Japanese had ‘astonished mankind’ and ‘placed Asia in a new light before the World’, [9] and he was right.

Richard Aldington’s earliest memories of Japan were from 1904 or 1905, when he and other British schoolboys wore small Japanese flags in their school-uniform buttonholes and prayed for Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War. [10] Later, when Aldington himself was sent to war, to the trenches of France in the winter of 1916, ‘one frosty night when the guns were still’ and he was ‘filled . . . with shrinking dread’ by the ‘ghostly scurrying of . . . rats / Swollen with feeding upon men’s flesh’, he pulled from his pack a notebook that contained transcriptions in his own hand of translations of poems from classical Japan, read them, then ‘leaned against the trench / Making for [himself] hokku / Of the moon and flowers and of the snow’. [11] Between those small flags on a school ground in the south of England and those small poems in a notebook at the Western Front lies a tale told by history, but it would be a mistake to believe that the narrative was linear, or the movement encompassed in its unfolding anything but contentious. To be sure the Japanese victory over Russia was acclaimed in Britain, and placed Japan in a new light in the public eye. Not only were the Tsar’s armies no longer a threat in China, but concerns that they might advance through the central Asian territories that separated Russia from India—the ‘standing nightmare of British foreign secretaries’, Hobsbawm calls it [12] —were moderated at Port Arthur and eliminated at Portsmouth, and public appreciation was genuine. Works by Japanese writers who sought to explain the spiritual basis for Japan’s success, most notably Yoshisaburô Okakura’s Japanese Spirit, introduced by George Meredith, and a newly-revised edition of Inazô Nitobe’s Bushido, [13] were widely read and much discussed, and even across the Atlantic some observers saw in the Japanese victory a cause for celebration. ‘Japan has advanced to the forefront of progressive open-mindedness’, the Universalist minister Sidney Gulick wrote in his Interpretation of . . . the Russo-Japanese War, and ‘now takes her part in doing the world’s work . . . to restrain the greedy aggressor and to build up the weak and backward’. [14]

But if American Universalists and British foreign secretaries saw in the Japanese victory a new hope for egalitarianism or an emancipation from fears that dark armies might advance down the Asian vales toward India, others established other positions in the newly-defined landscape. From a particular vantage point in the left foreground the Japanese appeared very like the saviours of a long-suffering anti-imperialist cause. Henry Hyndman’s journal Justice ‘rejoice[d]’ at the ‘Great Historic Event’ of the Japanese victory at Port Arthur, ‘because from one end of India to the other [the] . . . triumph will give the natives the fullest assurance that if they have even a tenth the pluck of the islanders of the Land of the Rising Sun, the days of English bloodsucking and famine-manufacture are coming to an end’. [15] And from an angle at the far right the contours of the landscape appeared in altogether different configurations. Among the most boisterous of those who adopted this position was T. W. H. Crosland, in a remarkable work of 1904 called The Truth about Japan, published in London by Grant Richards:

A stunted, lymphatic, yellow-faced heathen, with a mouthful of teeth three sizes too big . . . bulging slits where his eyes ought to be . . . a foolish giggle, a cruel heart, and the conceit of the devil—this, O bemused reader, is the authentic dearly-beloved ‘Little Jap’ . . . the fire-eater out of the Far East, and the ally, if you please, of John Bull, Esquire. [16]

Crosland granted that the Japanese had ‘dealt with Russia in a most convincing . . . manner’, and that ‘Europe at large was astounded, staggered and utterly taken aback’, but he would have none of the ‘unrestrained admiration’ for Japan to be found ‘in every newspaper in the kingdom’. After a series of maledictions about the proliferation of English writing of Japan (‘one long strain of undiluted patronage’), Japanese art (‘popular among the brainless’), Japanese poets (‘pygmies to a man’), and related matters, he arrived at the seriously-stated substance of his argument. The ‘spectacle’ of Japan’s victory over Russia ‘ought to be intolerable to European eyes’, Crosland wrote, for ‘Russia, after all, and in spite of her alleged barbarisms and faithlessness, is a white nation’, and ‘it is not seemly that a yellow race . . . should be permitted to bait her’; the ‘new world power notion’ therefore should ‘be knocked out of [the Japanese] forthwith’, for there ‘cannot be a world power which is other than white’, Crosland counselled, unless Europe would choose for itself ‘the sure way to Armageddon’. [17]

It would be irresponsible to suggest, as some writers have done, that a point of view such as Crosland’s represented mainstream opinion, or that a racist sub-text underlay the majority of English writing of Japan in this period, [18] but neither can it be denied that when Britain and America turned to Japan after 1905 the ideology of race was a more prominent feature of the landscape than before, or that in the United States a popular discourse that had hardened into policy in the Chinese Exclusion Acts of 1882-1902 became re-directed, with a new urgency and rancour, toward the Japanese. Japan’s victory over Russia ‘may have given a rude blow to the complacent assumption of the peoples of Europe and America that they were called upon to rule the world’, a widely-admired work of 1909 found, but ‘this has not altered a whit the determination of the Californian or Australian to keep his land . . . white’, at ‘any risk and . . . all cost’, whether ‘peacefully or by force’. [19] The acrimony of the American discourse as it addressed Japan after the Russo-Japanese War—the invocations of the Yellow Peril, the demagogic stances, the rhetorical de-humanisation of the nation—has been well documented, by Akira Iriye, Jean-Pierre Lehmann, Ian Littlewood, and John Dower, among others, [20] and need not be re-established here. The larger point in the context of this study is that by late 1905, after an absence that itself had engendered a singular response in the aesthetic landscape of France, Britain, and the United States, Japan had become for Europe and America an unprecedented non-Western presence, considered from positions across a range of points of view, on both sides of the Atlantic celebrated and despised but in conceptions of the relation of West and non-West impossible to ignore, or in any circumstance to imagine outside the context of the historical landscape from within which it had emerged, or the discursive landscape that had emerged from within that history.

Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War transformed the ways the West was able to see and to represent what was not of the West, and by extension the ways the West was able to see and to represent itself. In 1889 Japan may have been for Europe and the United States a Western invention and mode of style, as Wilde had it, but by the autumn of 1905 the Japanese had re-invented themselves in other terms, and Japan had emerged in the West, in something very like Karatani’s terms, as a landscape, a semiotic configuration that shaped the ways it was possible to perceive and to represent the world. If in August 1914 Europe entered a period of political, cultural, and aesthetic disjunction, a transition from one world to another, those who emerged on the other side and would turn to what was not of the West could do so, to adapt Karatani, only in terms that had been shaped by the epistemological constellation called Japan. No one would claim that the emergence of this Japan caused the disjunction of August 1914—though in strictly political terms Japan’s defeat of Russia facilitated an alliance that earlier had been unthinkable, the Triple Entente of Britain, Russia, and France that altered the political equilibrium of Europe and in Hobsbawm’s terms ‘turned the alliance system into a time bomb’ [21] —but Japan had entered the consciousness of the West in a way that undermined the orthodoxies of the world that was passing, and it should come as no surprise in this regard, to take but one of many possible examples, that when Ezra Pound undertook to challenge the orthodoxies of English verse in his Imagist and Vorticist manifestos of 1913-15 he would justify the positions he adopted explicitly in terms of the poetry, verse drama, and visual arts of Japan. [22] By August 1914 literary Japonisme had become a historical impossibility, but of necessity was giving way to something new. By that date when those with keen eyes and a reason for looking turned to what was not of the West they could not but see Japan, and many among them would carry over what they were able from that landscape into the landscape of the English literary tradition.

[1] Karatani Kôjin, Origins of Modern Japanese Literature, trans. Brett de Bary and others (Durham: Duke UP, 1993), pp. 18-34; translation of Nihon kindai bungaku no kigen (1980; reprint, Tokyo: Kodansha bungei bunko, 1995).

[2] The writers to whom reference is made are, respectively, S. Foster Damon (BH25b, 1918), Jun Fujita (A15, 1922), the anonymous author of a 1917 review of ‘Noh’ or Accomplishment (BK93a), Yoshiko Suetsugu (BL99, 1958), F. F. Farag (BL122, 1965), Hiro Ishibashi (BL131, 1966), Yasuko Stucki (BL134, 1966), Reiko Tsukimura (BL138, 1967), Masaru Sekine (BL233, 1986; BL247, 1989; BL250, 1990; BK207, 1995), Junko Nishiguchi (BH32, 1986), Emiko Yamaguchi (BI36, 1983), Richard Eugene Smith (BK111, 1965), Yukinobu Kagitani (BK127, 1970), Jyan-Lung Lin (BK196, 1992), Torao Taketomo (A8, 1920), and S. Ramaswamy (BL164, 1973).

[3] Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Empire (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1987), pp. 3-7.

[4] Ibid., pp. 70, 79.

[5] John Ruskin, ‘The Corruption of Modern Pleasure’, in Time and Tide (Orpington, Kent: Allen, 1882), p. 33.

[6] ‘Japan’, MacMillan’s Magazine 26 (1872): 496-97; ‘The Treaty Negotiations with Japan’, Times, 28 Dec. 1889, p. 6; ‘The New Era in Japan’, Times, 17 July 1899, p. 3.

[7] George Barlow, ‘Anglo-Japanese Treaty Sonnet’ (1902), in Poetical Works of George Barlow, vol. 10 (London: Glaisher, 1914), p. 224.

[8] Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Empire, pp. 79-80.

[9] Times, 11 Feb. 1904, quoted by Jean-Pierre Lehmann, The Image of Japan (1978, CC4), p. 15; Henry Hyndman, ‘Peace in the Far East’, Justice, 2 Sept. 1905, p. 1.

[10] Richard Aldington to Megata Morikimi, 16 May 1959 (BB15i), in ‘Richard Aldington’s Letters’ (1971, BB15), p. 70.

[12] Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Empire, p. 314.

[13] Inazô Nitobe, Bushido: The Soul of Japan, 10th ed. rev. (London: Putnam’s Sons, 1905); Yoshisaburô Okakura, The Japanese Spirit, introduction by George Meredith (London: Constable, 1905).

[14] Sidney L. Gulick, The White Peril in the Far East: An Interpretation of the Significance of the Russo-Japanese War (New York: Revell, 1905), pp. 115-16.

[15] ‘A Great Historic Event’, Justice, 7 Jan. 1905, p. 1.

[16] T. W. H. Crosland, The Truth about Japan (London: Richards, 1904), p. 1.

[17] Ibid., pp. 3, 8, 11, 30-31, 44, 57, 70-72.

[18] Authors whose work is collected in Phil Hammond, ed., Cultural Difference, Media Memories: Anglo-American Images of Japan (London: Cassell, 1997), for example, are willing to condemn as racist the bulk of Anglo-American writing about Japan from the mid-nineteenth century forward, though their over-reliance on secondary sources in discussion of early-century works is telling, as are frequent errors in matters as basic as the name of the American commander of the squadron to Uraga.

[19] Archibald Cary Coolidge, The United States as a World Power (New York: Macmillan, 1909), pp. 64, 353.

[20] Akira Iriye, ‘Japan as a Competitor, 1895-1917’ (1975, see CC12); Jean-Pierre Lehmann, The Image of Japan (1978, CC4); Ian Littlewood, The Idea of Japan (1996, CC10); John Dower’s War Without Mercy (1986) and Japan in War and Peace (1993, see CC12) include description of the ways the racist imagery of early-century re-surfaced in the years leading to and encompassing the Pacific War.

[21] Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Empire, pp. 313-15; the ‘first step towards the Triple Alliance’, Hobsbawm writes, was the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, ‘since the existence of that new power [Japan], which was soon to show that it could actually defeat the Tsarist Empire in war, diminished the Russian threat to Britain’ and ‘made the defusion of various ancient Russo-British disputes possible’ (p. 315).

[22]Ezra Pound, ‘A Few Don’ts for an Imagiste’, Poetry 1 (Mar. 1913, BK2); ‘How I Began’, T.P.’s Weekly, 6 June, 1913 (BK4); ‘Vortex’, Blast 1 (June 1914, BK10); ‘Edward Wadsworth, Vorticist’, Egoist 1 (Aug. 1914, BK11); ‘Vorticism’, Fortnightly Review NS 96 (Sept. 1914, BK12); ‘Affirmations II: Vorticism’, New Age 16/11 (Jan. 1915, BK14); ‘Affirmations IV: As for Imagisme’, New Age 16/13 (Jan. 1915, BK16); and ‘Affirmations VI: The “Image” and the Japanese Classical Stage’ (1915), Princeton University Library Chronicle 53/1 (1991, BK87).